Rifki Akbar Pratama· 19.06.25 · Review

Bahasa Indonesia · Deutsch

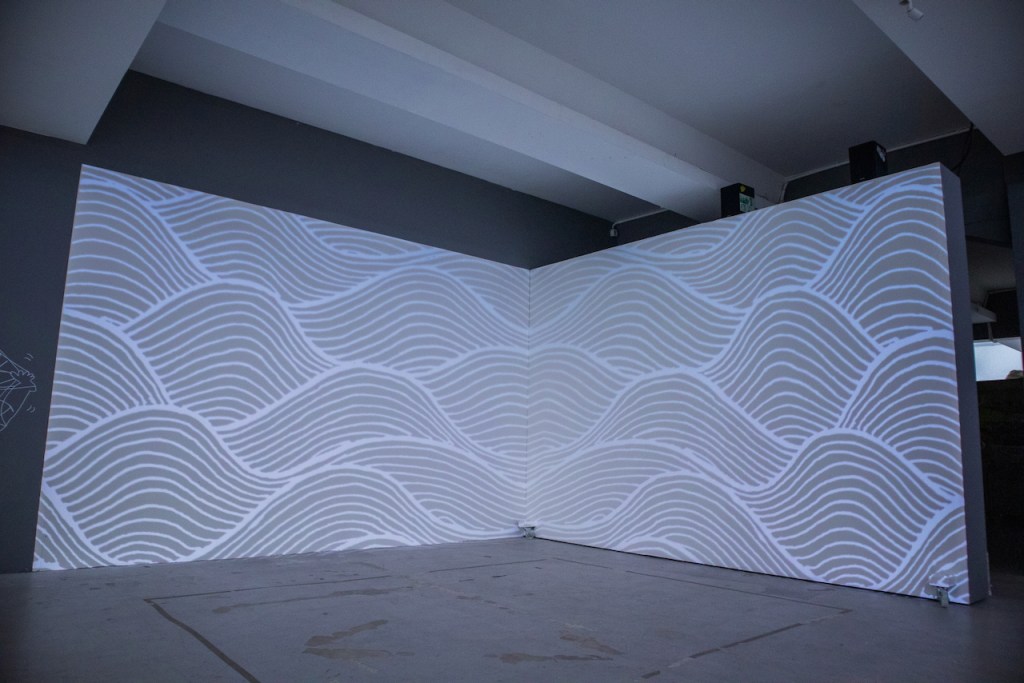

Rubanah Underground Hub Jakarta

May 27 – June 22 2025

The return of the invisible behind the veil of tactile articulation.

From the very beginning, we’ve been conditioned to believe that what’s valuable in art should be kept out of reach: the work behind the vitrine, the price list of each work, even all the idealism that inhabits the curatorial text. “No touching the works,” is a prohibition you encounter from the start. Not only in the barracks, even in the middle of an art gallery our bodies are monitored, regulated, restricted.

Touching is increasingly considered unusual and often problematic. April 2025, a child touches a Mark Rothko painting, and the world loses its mind. Ok, maybe go a little further: scratch. Not a few news articles included the price of Mark Rothko’s painting, around 927 billion. Concern was present in Rotterdam. Perhaps not so much about the boy as about the price of the painting slipping. A touch is considered a small sin that leads to a large fine. In the gallery, tactility is a transgression: a violation of the rules. It is a terror to form, order, even insurance policies. Why should the desire to touch, which arises as part of the way we experience art, be suppressed when it peaks in feeling?

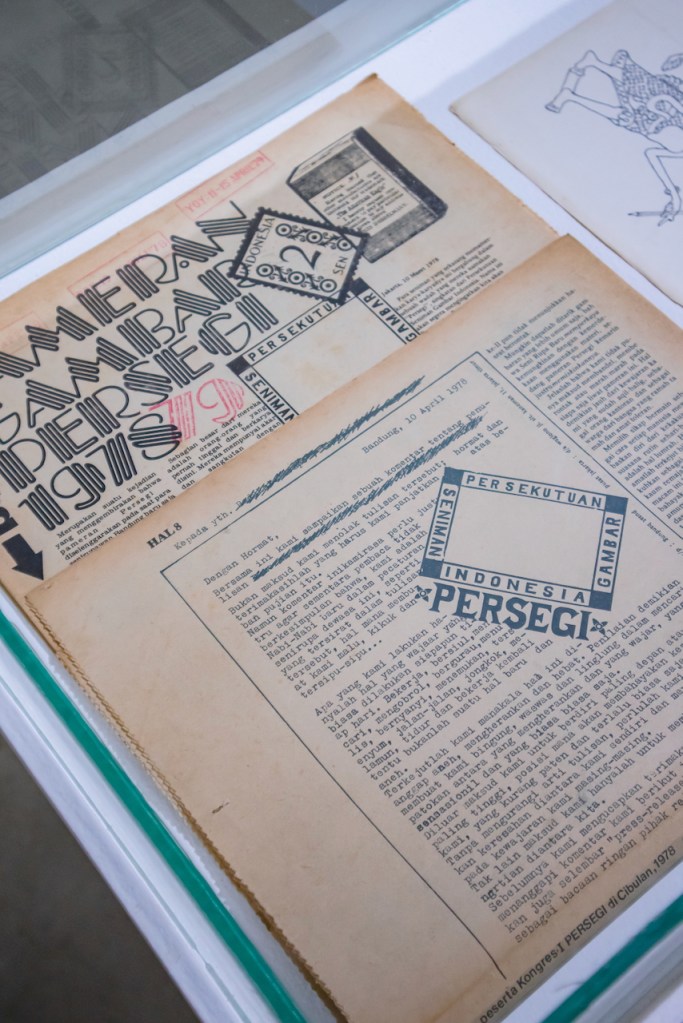

Similar questions could also be asked about the exhibition “Gion in Simulation” at RUBANAH Underground Hub. Wagiono Sunarto’s works may be two-dimensional and lack texture, except when the materiality of the work – such as the type of paper – allows it. However, traces of tactility are everywhere. Gion’s images may be flat, but they are also sticky. One example: The book illustration of the 1979 Indonesian New Art Movement, reproduced with acrylic paint on the surface of the pillars and walls of RUBANAH.

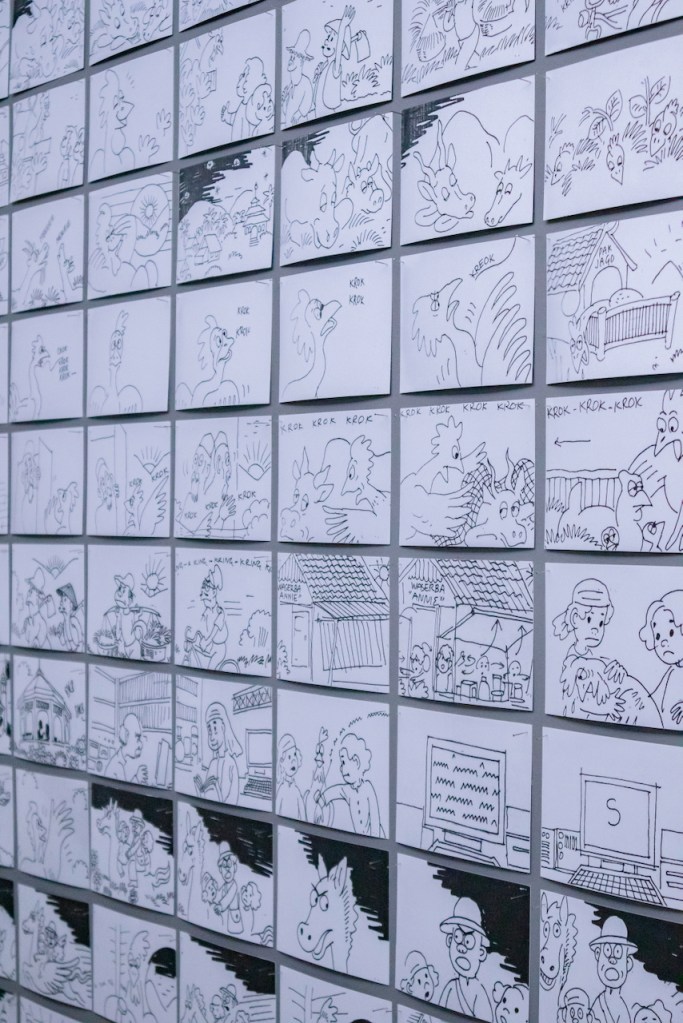

This series of Gion images shows the figure of a boy with a pinch of hair playing with a rope with rubber-like elasticity. On one of the poles perpendicular to the floor, the boy can be seen looking up at the star-like rubber-rope tangle that an adult hand is thrusting at him. On another pole, the boy sat sullenly with ropes wrapped around his arms and legs. Meanwhile, on the wall, he looks mischievously entangled by the rope around his own body. In the last picture, the boy appears to be having fun amidst the chaos of ten adults-in uncomfortable expressions amidst the same ropes-except for one adult wearing sunglasses who appears to be sharing the fun with him.

If we immerse the reading into the context of the Indonesian New Art Movement (GSRBI), we can draw a set of conclusions about the tension of intergenerational relations. Even if we attach it to the text that precedes the image in the GSRBI book published in 1979: “new forms” are not always born out of a spirit of renewal; they can also be born out of “free imagination”. However, that is not where we are going. This time we are going to answer another question, which may also ensnare the child: how does art ask for so much gaze but so little touch? It is also immersed in a kind of aesthetic paradox: when we are trained to feel deeply, to fade away and feel the texture, weight, closeness plus other things-but from a sacred distance. The kind of commandments and recommendations in religion. Art, in this case, is more afraid of being touched than misunderstood.

Accordingly, to allow touching is to share power. Because in the middle of the gallery, unless your touch is permitted – permitted because of your status – you are not allowed to touch, in the name of preservation. Although, the question of what is preserved, and who determines the conditions of preservation is not merely a matter of expertise but also a matter of power. It is a claim to proximity to history. A statement: I have a right here. In the case of “Gion in Simulation” there are two artists who offer a pattern of power redistribution and allow the return of tactility in the gallery space.

First: Ipeh Nur. Her installation Bukan Perang Hitam Putih, which crosses over Gion’s archival theme of the Mahabharata war, allows touch as a possibility. An index board that turns into a place for postcard-sized images and magnetized letters is placed in a row opposite another board-a metal plate on which pieces of similar images and letters are attached, arranged into one or two words that have been scrambled into a cipher. Visitors are allowed to shuffle them around and add and subtract from the pieces hidden behind the index shelf. One of the lines in his work is mesmerizing: “The gaze is the only thing that is always alive.” It is useful for crossing two things at once. How we respond to today’s work. Likewise, the issue of “war”-as a euphemism for genocide-is left unending and continues to hold us hostage as witnesses.

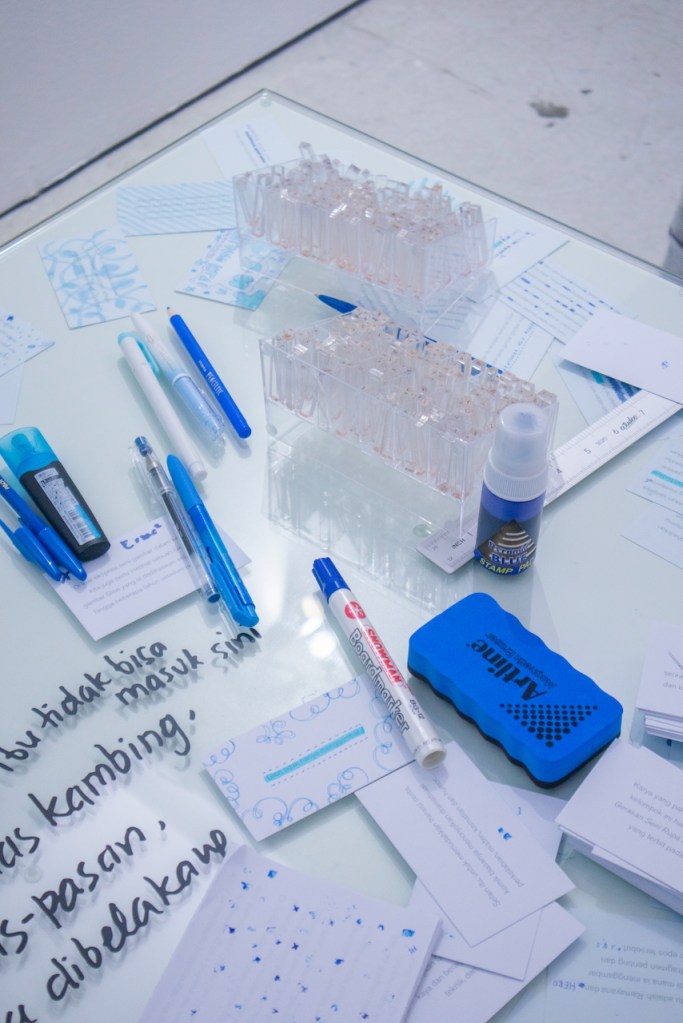

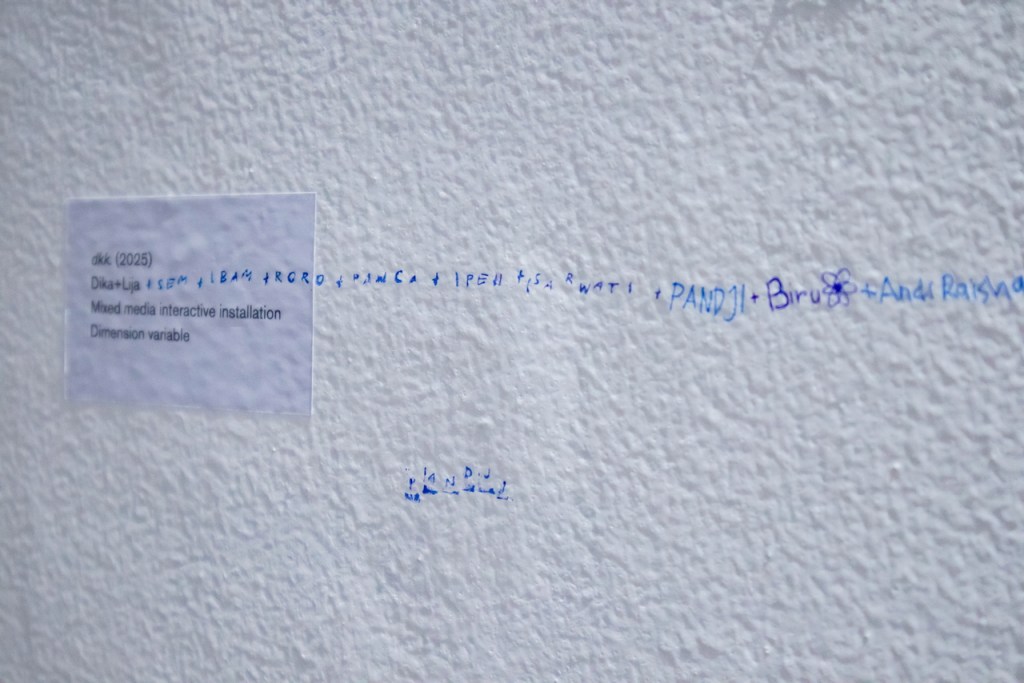

The second work, by Anathapindika Dai and Liza Markus (Dika+Lija) utilizes touch as part of the work. Dika and Lija place touch as an ellipsis (…) that spaces and invites visitors’ involvement to add, subtract, ignore, … – in short, intervene – pieces of curatorial words made by Chabib Duta Hapsoro. This premise of engagement naturally presents a cornucopia of options: testimonial notes, erata, other forms of work, and comedy. Everything can be changed and only one remains unwavering: the presence of a diversity of readings.

Based on openness to touch. Both succeeded in crossing the problem of simulation, as the framework of the exhibition, when other works stopped at the business of “presenting the results of simulation”. The two works just mentioned go further. Allowing touch, in both cases, means sharing rights and sharing power within the gallery space. Visitors are allowed to re-engineer images as well as texts, and thus ways of looking, in Ipeh’s work. It becomes important when we are often politely distanced from the reality of the screen: sensitive content, she says. A self-censorship that always asks for our consent to tap on the touchscreen. While with Dika and Lija, visitors are invited to question the things that often make our gaze narrow like a bottle neck in an art space: curatorial notes.

Keduanya, berhasil membawa kembali sentuhan sebagai gestur estetika yang ‘radikal’ dan tak melulu disepelekan sebagai gerak “kebocahan” yang apolitis. Pertanyaan sederhana yang ternyata usai ditanyakan ke beberapa pemirsa seni, tak mudah didapat jawabnya: apa karya seni yang terakhir kali kamu sentuh? Gestur sentuhan dalam karya mereka menandai secara tersirat atas rangkaian kuasa, eksklusi, juga pengaturan hasrat. Dalam gerak seni yang semakin imersif keduanya menjadi pengingat yang penting. Bahwa, sentuhan bukanlah pelanggaran, melainkan metode. Bahwa, bukan hanya soal membolehkan sentuhan yang penting, melainkan apa yang terjadi setelah kita menyentuh (dan mungkin, tersentuh oleh) karya seni yang menyadarkan kita atas adanya eksklusi. Itu tertuju bukan hanya untuk gerak-gerik kita di dalam ruang seni melainkan juga dalam kehidupan sehari-hari—yang semakin memerangkap kita ke dalam kejenuhan di dalam layar sentuh.

Rifki Akbar Pratama devotes himself to the confluence of history and psychology, the emotional histories of the left, intertemporal choice, and politics of affect as a researcher. Together with the Yogyakarta-based transdisciplinary research collective, KUNCI Study Forum & Collective, he dwells upon critical pedagogy, artistic practice, and knowledge production through the School of Improper Education program. His latest line of inquiry—shaped alongside Studio Malya and Reza Kutjh—engages historical memory-work through the gamified performance Yang Menyelinap Tak Mau Lesap (2025). His interest in publishing, in turn, ushered his work with Ufuk for the Jakarta Biennale 2021, where he examined the attention economy through collective, off-beat publishing.