Kezia C Y. Rantung · 06.08.25 · Review

Bahasa Indonesia · Deutsch

JNM Bloc Yogyakarta

March 16 – April 15 2025

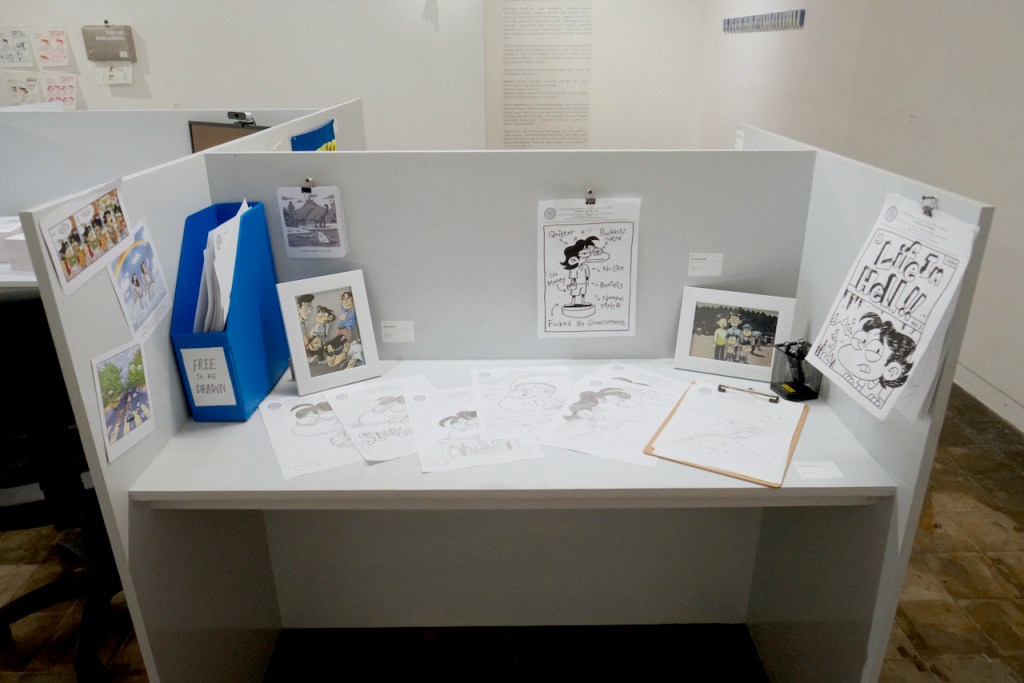

Myths about the ideal workplace are often passed down from generation to generation; a narrative of stability, productivity, and dedicated success. This myth developed from the long history of the cubicle, which has undergone transformations since the Renaissance era. Medieval European priests copied manuscripts using curtains, which then developed in the 19th century in modern bureaucratic environments, where offices began to implement a system of separating spaces based on function and hierarchy. Finally, in the 1960s, Robert Propst introduced cubicles as a solution to increase employee flexibility and productivity. However, in practice, cubicles have become a symbol of isolation and mechanization of the workforce.

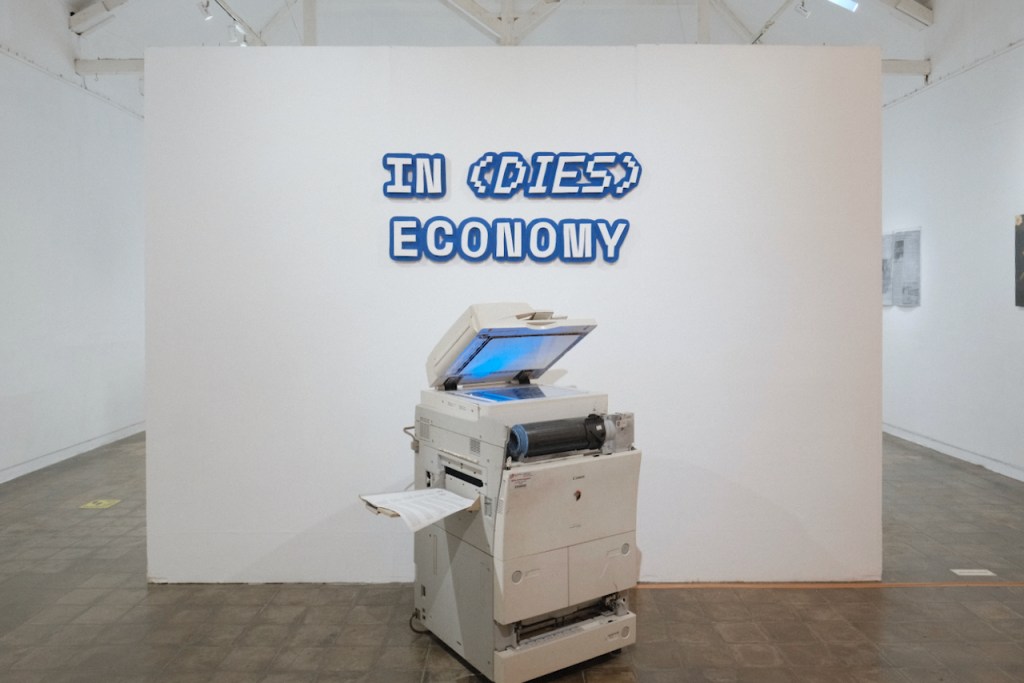

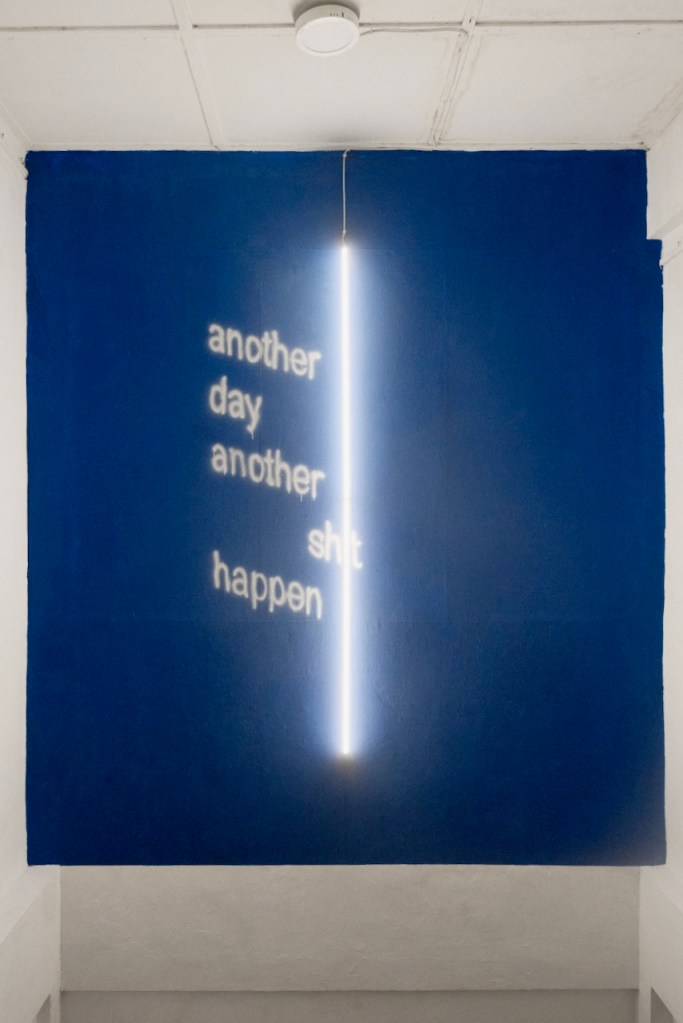

The exhibition titled “In (dies) Economy” by Titik Kumpul Forum & Collective explores how these myths are formed and operate in the current economic system, especially for Generation Z. In the hands of the young artists featured in this exhibition, the myth of an ideal working world is deconstructed. This exhibition invites us to re-examine the meaning of work in an ever-changing economic landscape, where workers face systemic uncertainty and digital expansion. In (dies) Economy offers a labyrinth as its main metaphor, with rooms that contain the artists’ speculations, leading visitors to the threshold of private and work spaces.

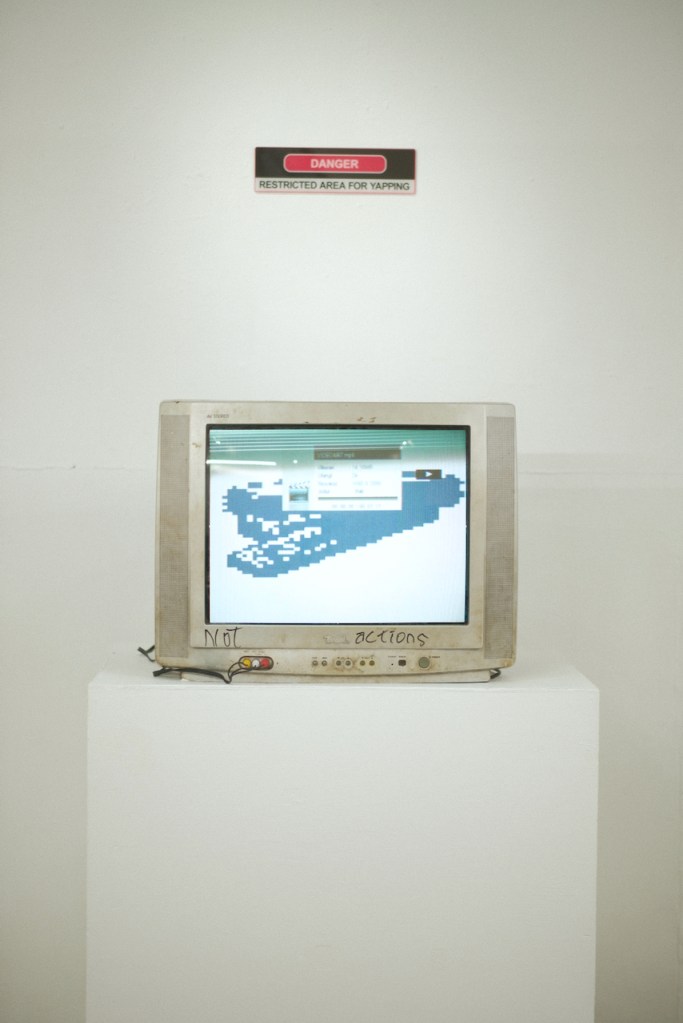

Each labyrinth expresses its anxiety in various forms: Kay Saputra (2025) offers manipulated images using digital techniques, resulting in large pixel images that obscure the meaning of the images. Additionally, Kay uses a computer screen with a camera that captures the movements of visitors sitting in front of it and converts them into a series of codes, distorting the image displayed on the screen to resemble broken glass. The work An Assortment of Pixelated Items reflects the increasingly digitized reality of work. Conceptually, pixelation symbolizes the loss of individual identity in a repetitive work system. Visitors observing this work are unconsciously involved in the process of decoding meaning, building understanding based on their personal experiences of the world of work. Meanwhile, Ason’s work (2025) uses paper media printed to resemble a newspaper with the title Dekonstruksi Pocong: Karangan Bunga Padi Tumbuh (Deconstruction of Pocong: Rice Flower Arrangement). Inside the booth, there is a shelf containing handmade newspapers, notebooks, ashtrays, and replica firearms. Ason expands his exploration of myths in a cultural and historical context.

By printing a handmade newspaper published in 2002 that narrates pocong as a scientific and political phenomenon, Ason invites the audience to reflect on how myths, whether about ghosts or work, are formed and passed down through the media. The newspaper displayed on the wall is blocked by iron wire, obscuring the text and reinforcing the idea that information always has a certain bias and construction that shapes our understanding. This work attempts to question the roots of language and words that have been believed by society from generation to generation. Next, in Tocka’s (2025) booth, he offers another speculation in the form of an installation made of grey (greige) fabric and thread that is sewn to resemble objects: a computer, mouse, keyboard, and voodoo doll. In addition, there is a reminder board that reads DAYS WITHOUT CRYING, March full of tears.

Tocka adds interactive elements to his work in the form of yellow fabric shaped like notes, each bearing the words “want,” “I,” “so,” “THEY,” “use,” “to,” and “do.” Visitors can rearrange these pieces, giving the impression that work experience is not static; it continues to change according to how we interpret it. The workspace presented by Tocka reflects the struggle to balance work and personal life.

This exhibition not only presents art as an aesthetic object but also as an active medium for dialogue in each room, with interactions presented in different characters. It is this interactive dimension that leads visitors into labyrinths full of speculation about work and space that can be negotiated, redefined, and even laughed at. The myth of the ideal workspace can also be broken through the courage to construct new meanings.

This writer and musician from Manado has published two books: “Wewene Sanggar Waktu” (A Collection of Minahasa Women’s Fairy Tales) and “Catatan-catatan yang Berserakan di Atas Ranjang” (Notes Scattered on the Bed).